Kaiserreich is the German term for a monarchical empire.

Literally a Kaiser’s Reich, an emperor’s domain or realm.

Frederick was a liberal and an admirer of the British constitution, while his links to Britain strengthened further with his marriage to Princess Victoria, eldest child of Queen Victoria.

With his ascent to the throne, many hoped that Frederick’s reign would lead to a liberalisation of the Reich and an increase of parliament’s influence on the political process.

The dismissal of Robert von Puttkamer, the highly-conservative Prussian interior minister, on 8 June was a sign of the expected direction and a blow to Bismarck’s administration.

By the time of his accession, however, Frederick had developed incurable laryngeal cancer, which had been diagnosed in 1887.

This decision led the ambitious Kaiser into conflict with Bismarck.

The old chancellor had hoped to guide Wilhelm as he had guided his grandfather, but the emperor wanted to be the master in his own house and had many sycophants telling him that Frederick the Great would not have been great with a Bismarck at his side.

Instead of condoning repression, Wilhelm had the government negotiate with a delegation from the coal miners, which brought the strike to an end without violence.

The fractious relationship ended in March 1890, after Wilhelm II and Bismarck quarrelled, and the chancellor resigned days later.

Bismarck’s last few years had seen power slip from his hands as he grew older, more irritable, more authoritarian, and less focused.

German politics had become progressively more chaotic, and the chancellor understood this better than anyone, but unlike Wilhelm II and his generation, Bismarck knew well that an ungovernable country with an adventurous foreign policy was a recipe for disaster.

With Bismarck’s departure, Wilhelm II became the dominant ruler of Germany.

Wilhelm became internationally notorious for his aggressive stance on foreign policy and his strategic blunders (such as the Tangier Crisis), which pushed the German Empire into growing political isolation.

_____________________________________________________________________

GERMAN ART, MUSIC, ARCHITECTURE and LITERATURE

|

‘William I Departs for the Front, July 31, 1870’

Adolph Menzel

|

ART

|

| Biedermeier Style |

‘Biedermeier’ refers to a style in literature, music, the visual arts and interior design in the period between the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and the revolutions of 1848.

Biedermeier art appealed to the prosperous middle classes by detailed but polished realism, often celebrating domestic virtues, and came to dominate over French-leaning aristocratic tastes, as well as the yearnings of Romanticism. Carl Spitzweg was a leading German artist in the style.

|

‘Eisenwalzwerk – Ironworks’

Adolph Menzel |

This style continued to be popular throughout the Kaiserreich and Wilhelmine period.

In the second half of the 19th century a number of styles developed, paralleling trends in other European counties, though the lack of a dominant capital city probably contributed to even more diversity of styles than in other countries.

Adolph Menzel enjoyed enormous popularity both among the German public and officialdom; at his funeral Kaiser Wilhelm II walked behind his coffin.

He dramaticised past and contemporary Prussian military successes both in paintings and brilliant wood engravings illustrating books, yet his domestic subjects are intimate and touching.

|

‘Coronation of Prince Wilhelm Friedrich Ludwig of Hohenzollern

as King Wilhelm I of Prussia – Schlosskirche, Königsberg’

Adolph Menzel |

His popularity in his native country, owing especially to politically propagandistic works, was such that few of his major paintings left Germany, as many were quickly acquired by museums in Berlin. Menzel’s graphic works and drawings were more widely disseminated; these, along with informal paintings not initially intended for display, have largely accounted for his posthumous reputation.

|

‘Hirtenknabe’

Franz von Lenbach |

Karl von Piloty was a leading academic painter of history subjects in the latter part of the century who taught in Munich.

Among his more famous pupils were Hans Makart, Franz von Lenbach, Franz Defregger, Gabriel von Max and Eduard von Grützner.

The term “Munich school” is used both of German and of Greek painting, after Greeks like Georgios Jakobides studied under him.

|

‘Gekreuzigten Diebe’

(Crucified Thief) – 1893

Lovis Corinth |

|

| Lovis Corinth – ‘Self Portrait’ |

The ‘Berlin Secession’ was a group founded in 1898 by painters including Max Liebermann, who broadly shared the artistic approach of Manet and the French Impressionists, and Lovis Corinth then still painting in a naturalistic style.

The group survived until the 1930s, despite splits, and its regular exhibitions helped launch the next two generations of Berlin artists, without imposing a particular style.

Near the end of the century, the Benedictine Beuron Art School developed a style, mostly for religious murals, in rather muted colours, with a medievalist interest in pattern that drew from Les Nabis and in some ways looked forward to Art Nouveau or the Jugendstil (“Youth Style”) as it is known in German.

|

‘Das Heilige Herz Jesu’

(The Sacred Heart of Jesus)

Wuger Steiner |

The Beuron art school was founded by a confederation of Benedictine monks in Germany in the late nineteenth century.

Beuronese art is principally known for its murals with “muted, tranquil and seemingly mysterious colouring”.

|

| ‘Sede Sapietiae’ |

Though several different principles were in competition to form the canon for the school, “the most significant principle or canon of the Beuronese school is the role which geometry played in determining proportions.” Lenz elaborated the philosophy and canon of a new artistic direction, which was based on the elements of ancient Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine and early Christian art.

Beuronese art had a large influence on the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt. In 1898, shortly after the beginning of the Vienna Secession, Father Desiderius Lenz had his book published – ‘Zur Aesthetic der Beuroner Schule’ (On the Aesthetics of the Beuron School). It is assumed that Klimt will have read Lenz’s work with enthusiasm and images of the Beuron Abbey, for instance, may show sections of the decorated ceiling which appear to have made quite a direct impact on Klimt’s decorative, golden paintings.

|

‘Kreuzigung’

(Crucifiction)

Franz von Stuck |

|

‘Geist des Sieges’

(The Spirit of Victory)

Franz von Stuck |

Two of the greatest artists of the Wilhelmine age were Franz von Stuck and Max Klinger – who today are often described as German Symbolists.

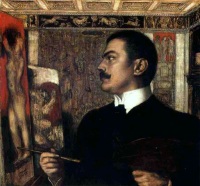

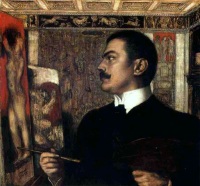

Franz Stuck (February 24, 1863 – August 30, 1928), ennobled as Franz Ritter von Stuck in 1906, was a German symbolist/Art Nouveau painter, sculptor, engraver, and architect.

Stuck’s subject matter was primarily from mythology, inspired by the work of Arnold Böcklin. Large forms dominate most of his paintings and indicate his proclivities for sculpture.

|

‘Selbstportrait’

Franz von Stuck |

His seductive female nudes are a prime example of popular Symbolist content.

Stuck paid much attention to the frames for his paintings and generally designed them himself with such careful use of panels, gilt carving and inscriptions that the frames must be considered as an integral part of the overall piece.

The number of Stuck’s pupils who achieved great success served to enhance the teacher’s own fame.

Yet by the time of his death, Stuck’s importance as an artist in his own right had lapsed.

Stuck’s reputation languished until the late 1960s when a renewed interest in Art Nouveau brought him to attention once more.

In 1968 the Villa Stuck was opened to the public; it is now a museum.

|

‘Der Arbend’

(Evening)

Max Klinger |

Max Klinger (February 18, 1857 – July 5, 1920) was a German Symbolist painter, sculptor, printmaker, and writer.

Klinger was born in Leipzig and studied in Karlsruhe.

An admirer of the etchings of Menzel and Goya, he shortly became a skilled and imaginative engraver in his own right.

He began creating sculptures in the early 1880s.

From 1883-1893 he lived in Rome, and became increasingly influenced by the Italian Renaissance and antiquity.

Ludwig Fahrenkrog is an example of the way that art, politics and religion became interwoven during the Wilhelmine period, leading up to the ‘Great war’.

|

‘Schicksal’

(Fate)

Ludwig Fahrenkrog |

Ludwig Fahrenkrog (20 October 1867 – 27 October 1952) was a German writer, playwright and artist.

He was born in Rendsburg, Prussia, in 1867.

He started his career as an artist in his youth, and attended the Berlin Royal Art Academy before being appointed a professor in 1913.

He taught at the School of Arts and Crafts in Bremen from 1898 to 1931.

He was also involved in the founding of a series of folkish religious groups in the early 20th century, as part of a movement to create what its adherents referred to as the Germanische Glaubens Gemeinschaft.

|

‘Die heilige Stunde’

(The Holy Hour)

Ludwig Fahrenkrog |

Fahrenkrog was trained in the classical tradition, and had a successful artistic career.

His style, however, was more dependent on Art Nouveau and Symbolist influences than on the classical tradition, and he always stressed the religious nature and mission of art.

|

Thule Swastika

German Faith Movement |

The “religious mission” in question is the revival of the pre-Christian Germanic faith and the rejection of Christianity, which is hinted at in paintings such as ‘Lucifer’s Lossage von Gott’ (Lucifer’s Renunciation of God, 1898).

While Fahrenkrog’s work can be seen in the context of contemporary art movements, it was also strongly influenced by his participation in the religious movement taking place at the same time.

The emblem of German Faith Movement was the curved (Thule) swastika, which was one of the first examples of the use of this symbol which was to be associated with the Dritte Reich.

|

‘Im walde – Des-Knaben Wunderhorn’

Moritz von Schwind |

|

‘Rose’

Moritz von Schwind |

There was a tendency in the Kaiserreich to idealize the middle ages.

This tendancy is to be found in literature, architecture (Ludwig II), and the visual arts.

Moritz von Schwind, (January 21, 1804 – February 8, 1871) although technically an Austrian, produced works for the German market, including the Bavarian king Ludwig II.

In 1834 he was commissioned to decorate King Ludwig’s new palace with wall paintings illustrating the works of the poet Tieck.

He also found in the same place congenial sport for his fancy in a “Kinderfries”.

He was often busy working on almanacs, and on illustrating Goethe and other writers through which he gained considerable recognition and employment.

In the revival of art in Germany, Schwind held as his own the sphere of poetic fancy.

MUSIC

|

| Wotan und Brunhilde |

Early in the 19th century, a composer by the name of

Richard Wagner was born.

He was a “Musician of the Future” who disliked the strict traditionalist styles of music.

He is credited with developing leitmotivs which were simple recurring themes found in his operas.

His music changed the course of opera, and of music in general, forever.

Wagner’s use of ancient German mythology in his ‘Ring’ cycle was a considerable boot to the growing nationalism of the Kaiserreich, and his last work, the sacred music drama ‘Parsifal’, created a link between German nationalism and quasi-Christian sentiments.

|

| Parsifal and the Flower Maidens |

In general the music of Wagner provided a strong stimulus for the emerging and developing Völkisch movement which had become fashionable among the educated middle and upper classes in the Kaiserreich.

The later 19th century saw Vienna continue its elevated position in European classical music, as well as a burst of popularity with Viennese waltzes.

These were composed by people like Johann Strauss the Younger.

Other German composers from the period included Albert Lortzing, Johannes Brahms, Robert Schumann, Felix Mendelssohn, Anton Bruckner, Max Bruch, Gustav Mahler, and the great Richard Strauss.

These composers tended to mix classic and romantic elements.

|

Salome – Richard Strauss

von Stuck |

|

| Richard Strauss |

Richard Georg Strauss (11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras.

He is known for his operas, which include ‘Der Rosenkavalier’ and ‘Salome’; his lieder, especially his ‘Four Last Songs’; and his tone poems and other orchestral works, such as ‘Death and Transfiguration’, ‘Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks’, ‘Also sprach Zarathustra’, ‘An Alpine Symphony’, Symphonia Domestica and ‘Metamorphosen’.

Strauss was also a prominent conductor throughout Germany and Austria.

Strauss represents the great late flowering of German Romanticism after Richard Wagner in which pioneering subtleties of orchestration are combined with an advanced harmonic style.

ARCHITECTURE

In architecture, Historicism (historismus), sometimes known as eclecticism, is an artistic and architectural style that draws inspiration from historic styles or craftmanship.

After the neo-classicist period (which could itself be considered a historicist movement), a new historicist phase emerged in the middle of the 19th century, marked by a return to a more ancient classicism, in particular in architecture and in the genre of history painting.

|

| Gottfried Semper |

|

| Münchner Festspielhaus |

An important architect of this period was Gottfried Semper, who built the gallery (1855) at the Zwinger Palace and the Semper Opera (1878) in Dresden.

The building has features derived from the Early Renaissance style, Baroque and even features Corinthian style pillars typical of classical Greece (classical revival).

There were regional variants of this style.

Examples are the resort architecture (especially on the German Baltic coast), the Hanover School of Architecture and the Nuremberg style.

|

| ‘Altes Museum’ – Karl Friedrich Schinkel |

Karl Friedrich Schinkel (13 March 1781 – 9 October 1841) was a Prussian architect, city planner, and painter who also designed furniture and stage sets.

Schinkel was one of the most prominent architects of Germany and designed both neoclassical and neogothic buildings, and was a strong influence on building styles in the Kaiserreich.

|

| Neue Wache – Karl Friedrich Schinkel |

Schinkel’s style, in his most productive period, is defined by a turn to Greek rather than Imperial Roman architecture, an attempt to turn away from the style that was linked to the recent French occupiers. (Thus, he is a noted proponent of the Greek Revival.)

His most famous buildings are found in and around Berlin.

These include Neue Wache (1816–1818),

The Neue Wache (“New Guard House”) is a building in Berlin. It is located on the north side of the ‘Unter den Linden’, a major east-west thoroughfare in the centre of the city.

|

| Schauspielhaus – Berlin – 1821 – Karl Friedrich Schinkel |

Dating from 1816, the Neue Wache was designed by the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, and is a leading example of German neoclassicism. Originally built as a guardhouse for the troops of the Crown Prince of Prussia, the building has been used as a war memorial since 1931.

National Monument for the Liberation Wars (1818–1821), the Schauspielhaus (1819–1821) at the Gendarmenmarkt, which replaced the earlier theatre that was destroyed by fire in 1817, and the ‘Altes Museum’ (old museum) on Museum Island (1823–1830).

He also carried out improvements to the Crown Prince’s Palace.

Later, Schinkel moved away from classicism altogether, embracing the Neo-Gothic in his Friedrichswerder Church (1824–1831).

The predilection for medieval buildings has its most famous exemplar in the castle of Neuschwanstein, which Ludwig II commissioned in 1869.

Neuschwanstein was designed by Christian Jank, a theatrical set designer, which possibly explains the fantastical nature of the resulting building.

Christian Jank (1833–1888), was a German scenic painter notable for his palace designs for King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

Jank was born on 15 July 1833 in Munich, the Bavarian capital.

Here he originally worked as a scenic painter. Among other things he was involved in the scenery for Richard Wagner’s opera Lohengrin. His work piqued the interest of Ludwig II, who commissioned him to create concepts for his architectural projects inspired by Wagner. Jank’s historistic drafts were the basis for Neuschwanstein Castle, which was built starting in 1869 by Eduard Riedel and later Georg von Dollmann. Jank was also involved in the interior of Linderhof Palace. His concepts for Falkenstein Castle could not be realized, as the project was abandoned after the king’s death in 1886. Jank himself died in Munich on 25 November 1888.

The architectural expertise, vital to a building in such a perilous site, was provided first by the Munich court architect Eduard Riedel and later by Georg Dollmann, son-in-law of Leo von Klenze.

There is also Ulm Cathedral, and at the end of the period the Reichstag building (1894) by Paul Wallot.

|

| ‘Jugend’ – January 1900 |

The Art Nouveau style is commonly known by its German name, Jugendstil.

Drawing from traditional German printmaking, the style uses precise and hard edges, an element that was rather different from the naturalistic style of the time.

The movement was centered in Hamburg

Within the field of Jugendstil art, there is a variety of different methods, applied by the various individual artists. Methods range from classic to romantic.

One feature that sets Jugendstil apart is the typography used, whose letter and image combination is unmistakable.

|

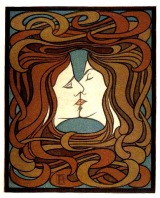

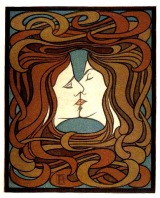

| ‘Der Kuss’ – Peter Behrens |

The combination was used for covers of novels, advertisements, and exhibition posters.

Designers often used unique display typefaces that worked harmoniously with the image.

Henry Van de Velde, who worked most of his career in Germany, was a Belgian theorist who influenced many others to continue in this style of graphic art including Peter Behrens, Hermann Obrist, and Richard Riemerschmid.

August Endell is another notable Art Nouveau designer.

Magazines were important in spreading the visual idiom of Jugendstil, especially the graphical qualities. Besides Jugend, other important ones were the satirical Simplicissimus and Pan.

Young Germany (Junges Deutschland) was a loose group of Vormärz writers which existed from about 1830 to 1850.

It was essentially a youth movement (similar to those that had swept France and Ireland and originated in Italy).

Its main proponents were Karl Gutzkow, Heinrich Laube, Theodor Mundt and Ludolf Wienbarg; Heinrich Heine, Ludwig Börne and Georg Büchner were also considered part of the movement.

The wider circle included Willibald Alexis, Adolf Glassbrenner and Gustav Kühne.

The so-called Biedermeier poets reacted by withdrawing into the realm of the family and idyllic nature.

|

| Heinrich Heine |

This resignation was replaced in the poems of Heinrich Heine by new political directions and a realistic outlook.

Many writers had to go into exile after the revolution of 1848, among them Karl Marx and Carl Schurz. Throughout the 19th century the forms introduced by Goethe and Schiller prevailed: in poetry, the Lied derived from folksongs; in drama, the historical tragedy in blank verse; in prose, the novella, an artistically structured story centered on an extraordinary event.

Annette Elisabeth von Droste-Hulshoff and Eduard Morike were the leading poets; Franz Grillparzer and Christian Friedrich Hebbel, the dramatists; Jeremias Gotthelf, Gottfried Keller, Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, Wilhelm Raabe, Adalbert Stifter, and Theodor Storm, the storytellers.

Far ahead of his time was Georg Buchner, who rejected bourgeois values and wrote such plays as Woyzeck (1850; Eng. trans., 1957), in which he anticipated modern styles.

|

| Georg Hegel |

Literature in the Reich was not only restricted to poetry, novels and biography, however.

Germany became, during this period, a world leader in philosophy.

Hegel was the precursor of these great philosophers.

He was followed by Arthur Schopenhauer, and later Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (August 27, 1770 – November 14, 1831) was a German philosopher, and a major figure in German Idealism.

His historicist and idealist account of reality revolutionized European philosophy. He was considered to be the ‘official philosopher’ of the Prussian State.

Hegel developed a comprehensive philosophical framework, or “system”, of Absolute idealism to account in an integrated and developmental way for the relation of mind and nature, the subject and object of knowledge, psychology, the state, history, art, religion, and philosophy.

In particular, he developed the concept that ‘mind’ or ‘spirit’ manifested itself in a set of contradictions and oppositions that it ultimately integrated and united, without eliminating either pole or reducing one to the other. This concept is known as dialectic.

|

| Arthur Schopenhauer |

Arthur Schopenhauer (22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher best known for his book, ‘Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung’, in which he claimed that our world is driven by a continually dissatisfied will, continually seeking satisfaction.

A key focus of Schopenhauer was his investigation of individual motivation. Before Schopenhauer, Hegel had popularized the concept of Zeitgeist, the idea that society consisted of a collective consciousness which moved in a distinct direction, dictating the actions of its members. Schopenhauer, a reader of both Kant and Hegel, criticized their logical optimism and the belief that individual morality could be determined by society and reason. Schopenhauer believed that humans were motivated by only their own basic desires, or Wille zum Leben (“Will to Live”), which directed all of mankind.

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (October 15, 1844 – August 25, 1900) was a German philosopher, poet, composer, cultural critic, and classical philologist.

He wrote critical texts on religion, morality, contemporary culture, philosophy, and science, displaying a fondness for metaphor, irony, and aphorism.

Nietzsche’s key ideas include the “death of God,” the ‘Übermensch’, ‘the eternal recurrence’, ‘the Apollonian and Dionysian dichotomy’, ‘perspectivism’, and ‘der Wille zur Macht’ (the will to power).

Central to his philosophy is the idea of “life-affirmation”, which involves questioning of all doctrines that drain life’s expansive energies, however socially prevalent those views might be.

His influence remains substantial within philosophy, notably in existentialism, post-modernism, and post-structuralism, as well as outside it.

His radical questioning of the value and objectivity of truth has been the focus of extensive commentary, especially in the continental tradition.

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

Physics – The work of Albert Einstein and Max Planck was crucial to the foundation of modern physics, which Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger developed further.

They were preceded by such key physicists as Hermann von Helmholtz, and Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit, among others.

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered X-rays, an accomplishment that made him the first winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901 and eventually earned him an element name, roentgenium.

|

| Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen |

|

| Heinrich Rudolf Hertz |

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz’s work in the domain of electromagnetic radiation were pivotal to the development of modern telecommunication.

Mathematical aerodynamics was developed in Germany, especially by Ludwig Prandtl.

At the start of the 20th century, Germany garnered fourteen of the first thirty-one Nobel Prizes in Chemistry, starting with Hermann Emil Fischer in 1901.

Numerous important mathematicians were born in Germany, including Gauss, Hilbert, Riemann, Weierstrass, Dirichlet and Weyl.

Germany has been the home of many famous inventors and engineers, such as Hans Geiger, the creator of the Geiger counter; and Konrad Zuse, who built the first computer.

|

| Gottlieb Daimler |

|

| Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin |

German inventors, engineers and industrialists such as Zeppelin, Daimler, Diesel, Otto, and Benz helped shape modern automotive and air transportation technology including the beginnings of space travel.

Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin (also known as Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin – 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a German general, and later aircraft manufacturer. He founded the Zeppelin Airship company. He was born in Konstanz, Grand Duchy of Baden (now part of Baden-Württemberg, Germany).

Gottlieb Daimler ( March 17, 1834 – March 6, 1900) was an engineer, industrial designer and industrialist born in Schorndorf (Kingdom of Württemberg, a federal state of the German Confederation), in what is now Germany. He was a pioneer of internal-combustion engines and automobile development. He invented the high-speed petrol engine and the first four-wheel automobile.

Alexander von Humboldt’s (1769–1859) work as a natural scientist and explorer was foundational to biogeography.

Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) was an eclectic Russian-born botanist and climatologist who synthesized global relationships between climate, vegetation and soil types into a classification system that is used, with some modifications, to this day.

Alfred Wegener (1880–1930), a similarly interdisciplinary scientist, was one of the first people to hypothesize the theory of continental drift which was later developed into the overarching geological theory of plate tectonics.

Wilhelm Wundt is credited with the establishment of psychology as an independent empirical science through his construction of the first laboratory at the University of Leipzig in 1879.

Sigmund Freud, who was in fact Austrian, was the inventor of the dream deutung.

Under Wilhelm II, Germany no longer had long-ruling strong chancellors like Bismarck.

The new chancellors had difficulty in performing their roles, especially the additional role as Prime Minister of Prussia assigned to them in the German Constitution.

The reforms of Chancellor Leo von Caprivi, which liberalized trade, and so reduced unemployment, were supported by the Kaiser and most Germans except for Prussian landowners, who feared loss of land and power and launched several campaigns against the reforms.

While Prussian aristocrats challenged the demands of a united German state, in the 1890s several organizations were set up to challenge the authoritarian conservative Prussian militarism which was being imposed on the country.

Educators opposed to the German state-run schools, which emphasized military education, set up their own independent liberal schools, which encouraged individuality and freedom, however nearly all the schools in Imperial Germany had a very high standard and kept abreast with modern developments in knowledge.

Artists began experimental art in opposition to Kaiser Wilhelm’s support for traditional art, to which Wilhelm responded “art which transgresses the laws and limits laid down by me can no longer be called art.”

It was largely thanks to Wilhelm’s influence that most printed material in Germany used ‘blackletter’ (fraktur) instead of the Roman type used in the rest of Western Europe.

At the same time, a new generation of cultural creators emerged.

From the 1890s onwards, the most effective opposition to the monarchy came from the newly formed Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), which advocated Marxism.

The threat of the SPD to the German monarchy and industrialists caused the state both to crack down on the party’s supporters and to implement its own programme of social reform to soothe discontent.

Germany’s large industries provided significant social welfare programmes and good care to their employees, as long as they were not identified as socialists or trade-union members.

The larger industrial firms provided pensions, sickness benefits and even housing to their employees.

Having learned from the failure of Bismarck’s Kulturkampf, Wilhelm II maintained good relations with the Roman Catholic Church and concentrated on opposing socialism.

This policy failed when the Social Democrats won ⅓ of the votes in the 1912 elections to the Reichstag, and became the largest political party in Germany.

|

| Feldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg |

|

| Generalquartiermeister Erich Ludendorff |

The government remained in the hands of a succession of conservative coalitions supported by right-wing liberals or Catholic clerics and heavily dependent on the Kaiser’s favour.

During World War I, the Kaiser increasingly devolved his powers to the leaders of the German High Command, particularly future President of Germany, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and Generalquartiermeister Erich Ludendorff.

Hindenburg took over the role of commander–in–chief from the Kaiser, while Ludendorff became de facto general chief of staff.

By 1916, Germany was effectively a military dictatorship run by Hindenburg and Ludendorff, with the Kaiser reduced to a mere figurehead.

Foreign Affairs

Wilhelm II wanted Germany to have her “place in the sun,” like Britain, which he constantly wished to emulate or rival.

With German traders and merchants already active worldwide, he encouraged colonial efforts in Africa and the Pacific (“new imperialism”), causing the German Empire to vie with other European powers for remaining “unclaimed” territories.

With the encouragement or at least the acquiescence of Britain, which at this stage saw Germany as a counterweight to her old rival France, Germany acquired German Southwest Africa (today Namibia), German Kamerun (Cameroon), Togoland and German East Africa (the mainland part of current Tanzania). Islands were gained in the Pacific through purchase and treaties and also a 99-year lease for the territory of Kiautschou in northeast China.

But of these German colonies only Togoland and German Samoa (after 1908) became self-sufficient and profitable; all the others required subsidies from the Berlin treasury for building infrastructure, school systems, hospitals and other institutions.

Bismarck had originally dismissed the agitation for colonies with contempt; he favoured a Eurocentric foreign policy, as the treaty arrangements made during his tenure in office show.

As a latecomer to colonization, Germany repeatedly came into conflict with the established colonial powers and also with the United States, which opposed German attempts at colonial expansion in both the Caribbean and the Pacific.

Native insurrections in German territories received prominent coverage in other countries, especially in Britain; the established powers had dealt with such uprisings decades earlier, often brutally, and had secured firm control of their colonies by then.

The Boxer Rising in China, which the Chinese government eventually sponsored, began in the Shandong province, in part because Germany, as colonizer at Kiautschou, was an untested power and had only been active there for two years.

Eight western nations, including the United States, mounted a joint relief force to rescue westerners caught up in the rebellion.

On two occasions, a French-German conflict over the fate of Morocco seemed inevitable.

Upon acquiring Southwest Africa, German settlers were encouraged to cultivate land held by the Herero and Nama. Herero and Nama tribal lands were used for a variety of exploitive goals (much as the British did before in Rhodesia), including farming, ranching, and mining for minerals and diamonds.

In 1904, the Herero and the Nama revolted against the colonists in Southwest Africa, killing farm families, their laborers and servants.

In response to the attacks, troops were dispatched to quell the uprising.

Middle East

Bismarck, and Wilhelm II after him, sought closer economic ties with the Ottoman Empire.

Under Wilhelm, with the financial backing of the Deutsche Bank, the Baghdad Railway was begun in 1900, although by 1914 it was still 500 km (310 mi) short of its destination in Baghdad.

In an interview with Wilhelm in 1899, Cecil Rhodes had tried “to convince the Kaiser that the future of the German empire abroad lay in the Middle East” and not in Africa; with a grand Middle-Eastern empire, Germany could afford to allow Britain the unhindered completion of the Cape-to-Cairo railway that Rhodes favoured.

Britain initially supported the Baghdad Railway; but by 1911 British statesmen came to fear it might be extended to Basra on the Persian Gulf, threatening Britain’s naval supremacy in the Indian Ocean. Accordingly they asked to have construction halted, to which Germany and the Ottoman Empire acquiesced.

Europe

Wilhelm II and his advisers committed a fatal diplomatic error when they allowed the “Reinsurance Treaty” that Bismarck had negotiated with Tsarist Russia to lapse.

Germany was left with no firm ally but Austria-Hungary, and her support for action in annexing Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908 further soured relations with Russia.

Wilhelm missed the opportunity to secure an alliance with Britain in the 1890s, when it was involved in colonial rivalries with France, and he alienated British statesmen further by openly supporting the Boers in the South African War and building a navy to rival Britain’s.

By 1911 Wilhelm had completely picked apart the careful power balance established by Bismarck and Britain turned to France in the Entente Cordiale.

Germany’s only other ally besides Austria was the Kingdom of Italy, but it remained an ally only pro forma. When war came, Italy saw more benefit in an alliance with Britain, France, and Russia, which, in the secret Treaty of London in 1915 promised it the frontier districts of Austria, where Italians formed the majority of the population, and also colonial concessions.

Germany did acquire a second ally that same year when the Ottoman Empire entered the war on its side, but in the long run supporting the Ottoman war effort only drained away German resources from the main fronts.

THE CAUSES OF THE ‘GREAT WAR’

The causes of World War I, which began in central Europe in late July 1914, included intertwined factors, such as the conflicts and hostility of the four decades leading up to the war. Militarism, alliances, imperialism, and nationalism played major roles in the conflict as well.

The immediate origins of the war, however, lay in the decisions taken by statesmen and generals during the Crisis of 1914, ‘casus belli’ for which was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife by Gavrilo Princip, an irredentist Serb.

The crisis came after a long and difficult series of diplomatic clashes between the Great Powers (Italy, France, Germany, the British Empire, the Austria-Hungarian Empire and Russia) over European and colonial issues in the decade before 1914 that had left tensions high.

In turn these diplomatic clashes can be traced to changes in the balance of power in Europe since 1867.

The more immediate cause for the war was tensions over territory in the Balkans.

Austria-Hungary competed with Serbia and Russia for territory and influence in the region, and they pulled the rest of the Great Powers into the conflict through their various alliances and treaties.

Background

In November 1912, Russia was humiliated because of its inability to support Serbia during the Bosnian crisis of 1908 – also known as the ‘First Balkan War’, and announced a major reconstruction of its military.

On November 28, German Foreign Secretary Gottlieb von Jagow told the Reichstag, that “If Austria is forced, for whatever reason, to fight for its position as a Great Power, then we must stand by her.“

As a result, British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey responded by warning Prince Karl Lichnowsky, the Germany Ambassador in London, that if Germany offered Austria a “blank cheque” for war in the Balkans, then “the consequences of such a policy would be incalculable.”

To reinforce this point, R. B. Haldane, the Germanophile Lord Chancellor, met with Prince Lichnowsky to offer an explicit warning that if Germany were to attack France, Britain would intervene in France’s favor.

With the recently announced Russian military reconstruction and certain British communications, the possibility of war was a leading topic at the German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912 in Berlin, an informal meeting of some of Germany’s top military leadership called on short notice by the Kaiser.

Attending the conference were Kaiser Wilhelm II, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz – the Naval State Secretary, Admiral Georg Alexander von Müller, the Chief of the German Imperial Naval Cabinet (Marinekabinett), General von Moltke – the Army’s Chief of Staff, Admiral August von Heeringen – the Chief of the Naval General Staff and General Moriz von Lyncker, the Chief of the German Imperial Military Cabinet.

The presence of the leaders of both the German Army and Navy at this War Council attests to its importance, however, Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg and General Josias von Heeringen, the Prussian Minister of War, were not invited.

Wilhelm II called British ‘balance of power’ concept “idiocy,” but agreed that Haldane’s statement was a “desirable clarification” of British policy.

His opinion was that Austria should attack that December and/ if “Russia supports the Serbs, which she evidently does…then war would be unavoidable for us, too,” and that would be better than going to war after Russia completed the massive modernization and expansion of their army that they had just begun. Moltke agreed.

In his professional military opinion “a war is unavoidable and the sooner the better“.

Moltke “wanted to launch an immediate attack“.

Both Wilhelm II and the Army leadership agreed that if a war were necessary it were best launched soon. Admiral Tirpitz, however, asked for a “postponement of the great fight for one and a half years” because the Navy was not ready for a general war that included Britain as an opponent.

He insisted that the completion of the construction of the U-boat base at Heligoland and the widening of the Kiel Canal were the Navy’s prerequisites for war.

The date for completion of the widening of the Kiel Canal was the summer of 1914.

Though Moltke objected to the postponement of the war as unacceptable, Wilhelm sided with Tirpitz. Moltke “agreed to a postponement only reluctantly.”

It should be noted that this War Council only showed the thinking and recommendations of those present, with no decisions taken.

Admiral Müller’s diary states: “That was the end of the conference. The result amounted to nothing.” Certainly the only decision taken was to do nothing.

With the November 1912 announcement of the Russian ‘Great Military Programme’, the leadership of the German Army began clamoring even more strongly for a “preventive war” against Russia.

Moltke declared that Germany could not win the arms race with France, Britain and Russia, which she herself had begun in 1911, because the financial structure of the German state, which gave the Reich government little power to tax, meant Germany would bankrupt herself in an arms race.

As such, Moltke from late 1912 onward was the leading advocate for a general war, and the sooner the better.

Throughout May and June 1914, Moltke engaged in an “almost ultimative” demand for a German “preventive war” against Russia in 1914.

The German Foreign Secretary, Gottlieb von Jagow, reported on a discussion with Moltke at the end of May 1914:

“Moltke described to me his opinion of our military situation. The prospects of the future oppressed him heavily. In two or three years Russia would have completed her armaments. The military superiority of our enemies would then be so great that he did not know how he could overcome them. Today we would still be a match for them. In his opinion there was no alternative to making preventive war in order to defeat the enemy while we still had a chance of victory. The Chief of the General Staff therefore proposed that I should conduct a policy with the aim of provoking a war in the near future.”

The new French President Raymond Poincaré, who took office in 1913, was favourable to improving relations with Germany.

In January 1914 Poincaré became the first French President to dine at the German Embassy in Paris.

Poincaré was more interested in the idea of French expansion in the Middle East than a war of revenge to regain Alsace-Lorraine.

Had the Reich been interested in improved relations with France before August 1914, the opportunity was available, but the leadership of the Reich lacked such interests, and preferred a policy of war to destroy France.

Because of France’s smaller economy and population, by 1913 French leaders had largely accepted that France by itself could never defeat Germany.

In May 1914, Serbian politics were polarized between two factions, one headed by the Prime Minister Nikola Pašić, and the other by the radical nationalist chief of Military Intelligence, Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević, known by his codename Apis.

In that month, due to Colonel Dimitrigjevic’s intrigues, King Peter dismissed Pašić’s government.

The Russian Minister in Belgrade intervened to have Pašić’s government restored.

Pašić, though he often talked tough in public, knew that Serbia was near-bankrupt and, having suffered heavy casualties in the Balkan Wars and in the suppression of a December 1913 Albanian revolt in Kosovo, needed peace.

Since Russia also favoured peace in the Balkans, from the Russian viewpoint it was desirable to keep Pašić in power.

It was in the midst of this political crisis that politically powerful members of the Serbian military armed and trained three Bosnian students as assassins and sent them into Austria-Hungary.

Domestic Political Factors

German Domestic Politics – Left-wing parties, especially the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) made large gains in the 1912 German election.

German government at the time was still dominated by the Prussian Junkers who feared the rise of these left-wing parties.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Junker was an often pejorative designation for a member of the landed nobility in Prussia and eastern Germany.

Supporting monarchism and military traditions, they were seen as reactionary, anti-democratic and protectionist. This political class held tremendous power over industrial classes and government alike.

It is possible that the Junkers deliberately sought an external war to distract the population and whip up patriotic support for the government.

Russia was in the midst of a large-scale military build-up and reform that they completed in 1916–17.

It is also argued, however, that German conservatives were ambivalent about a war, worrying that losing a war would have disastrous consequences, and even a successful war might alienate the population if it were lengthy or difficult.

French Domestic Politics – The situation in France was quite different from that in Germany as going to war appeared to the majority of political and military leaders to be a potentially costly gamble.

It is undeniable that forty years after the loss of Alsace-Lorraine a vast number of French were still angered by the territorial loss, as well as by the humiliation of being compelled to pay a large reparation to Germany in 1870.

The diplomatic alienation of France orchestrated by Germany prior to World War I caused further resentment in France.

Nevertheless, the leaders of France recognized Germany’s strong military advantage against them, as Germany had nearly twice as much population and a better equipped army.

At the same time, the episodes of the Tangier Crisis in 1905 and the Agadir Crisis in 1911 had given France a strong indication that war with Germany could be inevitable if Germany continued to oppose French colonial expansionism.

More than a century after the French Revolution, there was still a fierce struggle between the left-wing French government and its right-wing opponents.

Austria

In 1867, the Austrian Empire fundamentally changed its governmental structure, becoming the ‘Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary’.

For hundreds of years, the empire had been run in an essentially feudal manner, with a German-speaking aristocracy at its head, however, with the threat represented by an emergence of nationalism within the empire’s many component ethnicities, some elements, including Emperor Franz Joseph, decided that a compromise was required to preserve the power of the German aristocracy.

In 1867, the Ausgleich was agreed on, which made the Magyar (Hungarian) elite in Hungary almost equal partners in the government of Austria-Hungary.

This arrangement fostered a tremendous degree of dissatisfaction among many in the traditional German ruling classes.

Some of them considered the Ausgleich to have been a calamity, because it often frustrated their intentions in the governance of Austria-Hungary.

For example, it was extremely difficult for Austria-Hungary to form a coherent foreign policy that suited the interests of both the German and Magyar elite.

Throughout the fifty years from 1867 to 1914, it proved difficult to reach adequate compromises in the governance of Austria-Hungary.

At the same time, a form of social Darwinism became popular among many in the Austrian half of the government.

This thinking emphasised the primacy of armed struggle between nations, and the need for nations to arm themselves for an ultimate struggle for survival.

As a result, at least two distinct strains of thought advocated war with Serbia, often unified in the same people.

Some reasoned that dealing with political deadlock required that more Slavs be brought into Austria-Hungary to dilute the power of the Magyar elite.

With more Slavs, the South Slavs of Austria-Hungary could force a new political compromise in which the Germans could play the Magyars against the South Slavs.

Another fear was that the South Slavs, primarily under the leadership of Serbia, were organizing for a war against Austria-Hungary, and even all of Germanic civilization.

Some leaders, such as Conrad von Hötzendorf, argued that Serbia must be dealt with before it became too powerful to defeat militarily.

A powerful contingent within the Austro-Hungarian government was motivated by these thoughts and advocated war with Serbia long before the war began.

Prominent members of this group included Leopold von Berchtold, Alexander von Hoyos, and Johann von Forgách.

Although many other members of the government, notably Franz Ferdinand, Franz Joseph, and many Hungarian politicians did not believe that a violent struggle with Serbia would necessarily solve any of Austria-Hungary’s problems, the hawkish elements did exert a strong influence on government policy, holding key positions.

It is important to understand the

central role of Austria-Hungary in

starting the war.

Convinced Serbian nationalism and Russian Balkan ambitions were disintegrating the Empire, Austria-Hungary hoped for a limited war against Serbia and that strong German support would force Russia to keep out of the war and weaken its Balkan prestige.

Imperialism

Some attribute the start of the war to imperialism.

Countries such as the United Kingdom and France accumulated great wealth in the late 19th century through their control of trade in foreign resources, markets, territories, and people.

Other empires, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Russia all hoped to do so as well in economic advantage.

Their frustrated ambitions, and British policies of strategic exclusion created tensions.

In addition, the limits of natural resources in many European nations began to slowly alter trade balance, and make national industries seek new territories rich in natural resources.

Commercial interests contributed substantially to Anglo-German rivalry during the scramble for tropical Africa.

This was the scene of sharpest conflict between certain German and British commercial interests.

There have been two partitions of Africa.

One involved the actual imposition of political boundaries across the continent during the last quarter of the 19th century; the other, which actually commenced in the mid-19th century, consisted of the so-called ‘business’ partition.

In southern Africa the latter partition followed rapidly upon the discoveries of diamonds and gold in 1867 and 1886 respectively.

An integral part of this second partition was the expansion in the interior of British capital interests, primarily the British South Africa Company and mining companies such as De Beers.

After 1886 the Witwatersrand goldfields prompted feverish activity among European as well as British capitalists.

It was soon felt in Whitehall that German commercial penetration in particular constituted a direct threat to Britain’s continued economic and political hegemony south of the Limpopo.

Amid the expanding web of German business on the Rand, the most contentious operations were those of the German-financed N.Z.A.S.M. or Netherlands South African Railway Company, which possessed a railway monopoly in the Transvaal.

Rivalries for not just colonies, but colonial trade and trade routes developed between the emerging economic powers and the incumbent great powers.

|

| Berlin-Baghdad Railway |

This rivalry was illustrated in the Berlin-Baghdad Railway, which would have given German industry access to Iraqi oil, and German trade a southern port in the Persian Gulf.

A history of this railroad in the context of World War I has arrived to describe the German interests in countering the British Empire at a global level, and Turkey’s interest in countering their Russian rivals at a regional level.

‘It was felt in England that if, as Napoleon is said to have remarked, Antwerp in the hands of a great continental power was a pistol leveled at the English coast, Bagdad and the Persian Gulf in the hands of Germany (or any other strong power) would be a 42-centimetre gun pointed at India.’

On the other side, “Public opinion in Germany was feasting on visions of Cairo, Baghdad, and Tehran, and the possibility of evading the British blockade through outlets to the Indian Ocean.”

Britain’s initial strategic exclusion of others from northern access to a Persian Gulf port in the creation of Kuwait by treaty as a protected, subsidized client state showed political recognition of the importance of the issue.

If outcome is revealing, by the close of the war this political recognition was re-emphasized in the military effort to capture the railway itself, recounted with perspective in a contemporary history: “On the 26th Aleppo fell, and on the 28th we reached Muslimieh, that junction on the Baghdad railway on which longing eyes had been cast as the nodal point in the conflict of German and other ambitions in the East.”

The Treaty of Versailles explicitly removed all German ownership thereafter, which without Ottoman rule left access to Mesopotamian and Persian oil, and northern access to a southern port in British hands alone.

|

| Otto von Bismarck |

Rivalries among the great powers were exacerbated starting in the 1880s by the scramble for colonies, which brought much of Africa and Asia under European rule in the following quarter-century.

It also created great Anglo-French and Anglo-Russian tensions and crises that prevented a British alliance with either until the early 20th century.

Otto von Bismarck disliked the idea of an overseas empire, but pursued a colonial policy to court domestic political support.

This started Anglo-German tensions since German acquisitions in Africa and the Pacific threatened to impinge upon British strategic and commercial interests.

Bismarck supported French colonization in Africa because it diverted government attention and resources away from continental Europe and revanchism.

In spite of all of Bismarck’s deft diplomatic maneuvering, in 1890 he was forced to resign by the new Kaiser (Wilhelm II).

His successor, Leo von Caprivi, was the last German Chancellor who was successful in calming Anglo-German tensions.

|

| Leo von Caprivi |

After his loss of office in 1894, German policy led to greater conflicts with the other colonial powers.

The status of Morocco had been guaranteed by international agreement, and when France attempted to greatly expand its influence there without the assent of all the other signatories Germany opposed it prompting the ‘Moroccan Crise’s, the ‘Tangier Crisis’ of 1905 and the ‘Agadir Crisis’ of 1911.

The intent of German policy was to drive a wedge between the British and French, but in both cases produced the opposite effect, and Germany was isolated diplomatically, most notably lacking the support of Italy despite Italian membership in the Triple Alliance.

The French protectorate over Morocco was established officially in 1912.

In 1914, there were no outstanding colonial conflicts, Africa essentially having been claimed fully, apart from Ethiopia, for several years, however, the competitive mentality, as well as a fear of “being left behind” in the competition for the world’s resources may have played a role in the decisions to begin the conflict.

The Arms Race

A self-reinforcing cycle of heightened military preparedness…was an essential element in the conjuncture that led to disaster…The armaments race…was a necessary precondition for the outbreak of hostilities.

If Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated in 1904 or even in 1911, there might have been no war. It was…the armaments race…and the speculation about imminent or preventive wars that made his death in 1914 the trigger for war.

Some historians see the German naval build-up as the principal cause of deteriorating Anglo-German relations.

The overwhelming British response, however, proved to Germany that its efforts were unlikely to equal the Royal Navy.

In 1900, the British had a 3.7:1 tonnage advantage over Germany; in 1910 the ratio was 2.3:1 and in 1914, 2.1:1.

So decisive was the British victory in the naval arms race that it is hard to regard it as in any meaningful sense a cause of the First World War.

This ignores the fact that the Kaiserliche Marine had narrowed the gap by nearly half, and that the Royal Navy had long intended to be stronger than any two potential opponents; the United States Navy was in a period of growth, making the German gains very ominous.

Technological changes, with oil- rather than coal-fuelled ships, decreasing refuelling time while increasing speed and range, and with superior armour and guns also would favour the growing, and newer, German fleet.

One of the aims of the ‘First Hague Conference’ of 1899, held at the suggestion of Russian Emperor Nicholas II, was to discuss disarmament.

The ‘Second Hague Conference’ was held in 1907.

All the signatories except for Germany supported disarmament.

Germany also did not want to agree to binding arbitration and mediation.

The Kaiser was concerned that the United States would propose disarmament measures, which he opposed.

Russian interests in Balkans and Ottoman Empire

The main Russian goals included strengthening its role as the protector of Eastern Christians in the Balkans (such as the Serbians).

Although Russia enjoyed a booming economy, growing population, and large armed forces, its strategic position was threatened by an expanding Turkish military trained by German experts using the latest technology.

The start of the war renewed attention of old goals: expelling the Turks from Constantinople, extending Russian dominion into eastern Anatolia and Persian Azerbaijan, and annexing Galicia.

These conquests would assure Russian predominance in the Black Sea.

Over by Christmas

|

Field Marshal Lord

Horatio Herbert Kitchener |

Both sides believed, and publicly stated, that the war would end soon.

The Kaiser told his troops that they would be, “…home before the leaves have fallen from the trees,” and one German officer said he expected to be in Paris by Sedantag, about six weeks away.

Germany only stockpiled enough potassium nitrate for gunpowder for six months.

Russian officers similarly expected to be in Berlin in six weeks, and those who suggested that the war would last for six months were considered pessimists.

Von Moltke and his French counterpart Joseph Joffre were among the few who expected a long war, but neither adjusted his nation’s military plans accordingly.

The new British Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, was the only leading official on either side to both expect a long war (“three years” or longer, he told an amazed colleague) and act accordingly, immediately building an army of millions of soldiers who would fight for years.

Schlieffen Plan

|

|

Alfred Graf von Schlieffen |

Germany’s strategic vulnerability, sandwiched between its allied rivals, led to the development of the audacious (and incredibly expensive) Schlieffen Plan.

It aimed to knock France instantly out of contention, before Russia had time to mobilize its gigantic human reserves.

It aimed to accomplish this task within 6 weeks.

Germany could then turn her full resources to meeting the Russian threat.

Although Count Alfred von Schlieffen initially conceived the plan before his retirement in 1906, Japan’s defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 exposed Russia’s organizational weakness and added greatly to the plan’s credibility.

The plan called for a rapid German mobilization, sweeping through the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Belgium, into France.

Schlieffen called for overwhelming numbers on the far right flank, the northernmost spearhead of the force with only minimum troops making up the arm and axis of the formation as well as a minimum force stationed on the Russian eastern front.

|

| Helmuth von Moltke |

Schlieffen was replaced by Helmuth von Moltke, and in 1907–08 Moltke adjusted the plan, reducing the proportional distribution of the forces, lessening the crucial right wing in favor of a slightly more defensive strategy.

Also, judging Holland unlikely to grant permission to cross its borders, the plan was revised to make a direct move through Belgium, and an artillery assault on the Belgian city of Liège.

With the rail lines and the unprecedented firepower the German army brought, Moltke did not expect any significant defense of the fortress.

The significance of the Schlieffen Plan is that it forced German military planners to prepare for a pre-emptive strike when war was deemed unavoidable.

Otherwise Russia would have time to mobilize and crush Germany with its massive army.

On August 1, Kaiser Wilhelm II briefly became convinced that it might be possible to ensure French and British neutrality, and cancelled the plan despite the objections of the Chief of Staff that this could not be done, and resuming it only when the offer of a neutral France and Britain was withdrawn.

It appears that no war planners in any country had prepared effectively for the Schlieffen Plan.

The French were not concerned about such a move. They were confident their offensive (Plan XVII) would break the German center and cut off the German right wing moving through Belgium.

They also expected that an early Russian offensive in East Prussia would tie down German forces.

Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

Richard Georg Strauss (11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was undoubtedly the leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras.

Richard Georg Strauss (11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was undoubtedly the leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras.